Academic flatlining.

Why we are barking up the wrong tree on educational ‘decline’.

Bucking the trend.

Australian news stories love to talk about the schools “bucking the trend”.

It’s a classic hero story, where the valiant leader takes charge to turn a school around from educational mediocrity to becoming a shining beacon of teaching practice.

This is not a bad thing. It is right that we celebrate the important work being done in schools across the country.

However, there seems to be an underlying assumption within such narratives that educational problems are area-specific and are largely due to deficiencies in local teachers, leaders or systems.

It is assumed that all that schools need is the right leader, model or program to turn things around.

This kind of thinking extends more broadly at a national scale, as governments increasingly scrutinise local systems for shortfalls contributing to the perceived deterioration of Australia’s educational standing across the world. Never forget our obsession with competition, even when it has perverse implications for education.

Global, not national, developments.

The idea that problems have a local explanation and therefore need a local solution is often wrong, despite being widespread. Examples abound.

After the pandemic, many countries went through an inflation spike. Globally there was sustained criticism of local politicians, including in Australia, arguing that they hadn’t done enough to keep inflation lower. But if every country in the world suffered from an inflation spike – largely due to the pent up demand from the pandemic years – a national explanation for it’s cause makes little sense. No single country was able to stop the pandemic and no single country was able to reign in inflation. The sheer number of nationally-based arguments about inflation makes us wonder if anyone really follows international news. The inflation spike was covered widely in the media, and yet the federal government was regularly challenged about why it had ‘caused’ inflation. It hadn’t; it was a global phenomenon that was only fixed when global economic conditions changed.

Likewise with obesity rates. We hear people asking why Australians are becoming more obese, when a quick glance at an international measure shows that this same increase is occurring everywhere in the developed world.

The same is true of the calamitous mental health drop amongst youth since about 2015. There are regular bouts of hand wringing about the reduction in mental health of Australian youth. Yet we know that this is a global, not specifically Australian, problem.

The same can be said about other global phenomena that no doubt also have a local flavour: housing affordability, energy price increases, public sector worker shortages (notably teachers and nurses), birth rate declines and productivity slowdowns.

Global academic achievement has stalled, it is not a peculiarly Australian phenomenon.

The blame game.

On the assumption that we agree that things need to change, who is responsible for turning education around?

There is a growing current trend in educational discourse to frame teachers, schools and universities as the cause of Australia’s educational woes. This results in an ideological in-house blame game, where we scramble to find convincing evidence to show which teachers, universities or schools in Australia are holding education back. As a result, particular pedagogies are now becoming mandated, and teacher training is going through yet more compulsory reform, all under the assumption that it is Australia that has a problem with K-12 student academic achievement.

These approaches are ideological in the sense that it is assumed that it is the local teacher, leader, school who is responsible for changing things. We have met many educators who admirably take it upon themselves to change things. The $10 million “Be That teacher” campaign is an excellent example of how such ideological perspectives are reinforced, whilst leaving their underlying assumptions unquestioned.

Let’s take a second to step back here.

What if we were to suggest that the educational problems Australia is facing are not unique to Australia, but are symptoms of broader, global trends?

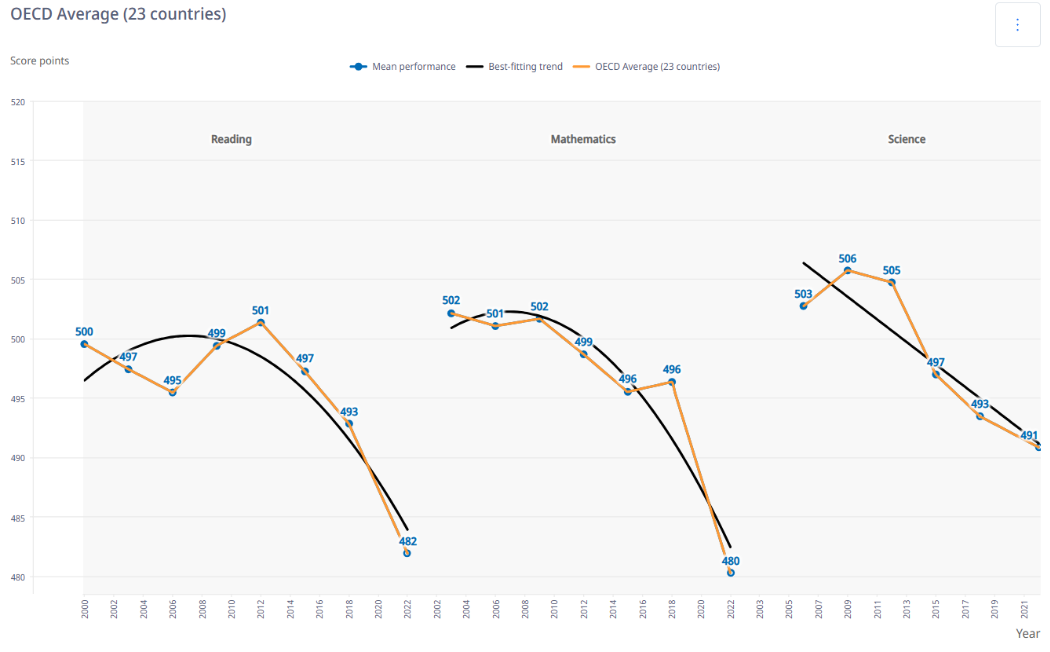

For example, global performance in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) performance have been on the decline over the past 20 years.

If educational decline is not an Australia-specific problem, what are the global tendencies that lead to it?

The changing experience of modern youth.

We know the mental health of youth has dramatically dropped in the last decade. Debate continues to rage over what the cause of this is, but many of the changes to the experience of young people could all be part of the explanation: rise in screen use, decrease in physical activity, increase in social media use, drop in the amount of time spent in person with others, rise in loneliness, increase in working hours of parents and a myriad of cultural changes (rise in sexism, youth-culture obsession, reduction in respect).

In one generation we have gone from children doing chores and playing on the streets to gentle parenting and only adult-supervised and costly after school activities. Teens themselves report being online ‘almost constantly’.

Do we honestly think we can tackle issues of this magnitude at the national level? The state level? The single school level?

If the cause of the drop in educational achievement is global, solutions might need to be as well. Or at least, we could be able to come up with better solutions by working across national borders, rather than assuming all the best solutions are home grown. Social media use by youth, for example, is better tackled globally. Not only are young people easily able to circumvent any social media bans through VPNs, but many tech giants play countries off against one another in an effort to keep conditions in their favour – think Google and Meta when they fought back against Australian attempts to get them to pay for the locally-generated news they were sharing.

We need to work with our international educational partners to determine causes and suggestions for solutions.

Where’s the village?

They say it takes a village to raise a child.

Where has the village gone?

We need to consider how everyone has a responsibility for turning around education. This is a worldly problem. All parties have a stake in its success, and all parties must consider what role they have in contributing to the educational problems we’re seeing globally and how they might address them.

It’s easy to blame something or someone, but we cannot move forward if we simply seek to divert blame to a single cause.

The school is in no way the dominant influence in young people’s lives anymore and as stated earlier, this is not an Australia-specific experience. We must acknowledge the broader education that is happening beyond the school, mediated through for-profit algorithms. A recent report by the Black Dog Institute found that almost a third of young people are spending over four hours a day on social media.

How can we possibly place the total responsibility for academic decline upon teachers, schools or universities in such an environment?

Unlike the OECD’s approach that suggests that education systems ought to adapt in response to global trends and forces impacting on education, we should instead be considering how broader areas of influence contribute to educational issues.

Mental health issues, increasing polarisation and rising inequality will not be solved by education alone.

Education sits within, and is subject to, the structural forces that press upon it, with many of these forces now visible on a global scale.

Maybe it’s time for education to push back.

Till next time,

Thanks for this article. The current landscape reminds me of the quote "never let a crisis go to waste"(Churchill?)It's much easier to give the appearance of doing something by laying blame and responsibility on teachers, schools, training institutions rather than address the much broader social and economic issues. The trickle down effect is then increasing reliance on magical commercial programs and rising levels of micro management all in an effort to appear to be doing something. Not to mention the amplification of the message "teachers don't know what they're doing so we the *experts* will tell them.We must keep up these conversations of going back to the big picture and ideologies.

Wanted to foreground this bit: “The idea that problems have a local explanation and therefore need a local solution is often wrong, despite being widespread. Examples abound.”

It’s a mental grappling hook for me. I first read this piece a few days ago and paused right at that quote — then got distracted and didn’t come back until it resurfaced in my LinkedIn feed. Now it’s pulled me back in.

Another thread that’s been looping in my mind is how the “problems of/in education” might not be our fault — and how that idea keeps finding space in my brain to ruminate.

This may just be one of those Substacks I need to come back to again and again. Thanks for the share.