The encounter with the face of the other is a command that tells us all, uncomfortably, that we are our brother and sister's keepers - Emmanuel Levinas

This year, data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics showed that despite cost-of-living pressures and the declining percentage of Australians identifying as religious, private school enrolments have “soared for the third straight year.” There are many reasons behind this trend. Parents consider factors such as facilities, a school’s reputation, approaches to discipline, or their perception that private schools have better values. Dr Adrian Beavis writes that “the strongest effect on the selection of a private school [is] the importance parents attach to the perception of the school having traditional values.”

Many parents, such as mother Wendy Boquest, have described making huge “financial sacrifices” to send their children to a private school because the “opportunities, values, and community” are “incomparable.” Indeed, private and public schools are typically “incomparable” when it comes to facilities and funding, and most people know this already. For instance, last week it was revealed that three of Sydney’s wealthiest private schools received double the federal funding they were entitled to in 2023.

The belief that private schools have a more pristine embedded set of values than public schools is entrenched and must be challenged because it is untrue and offensive.

But if one of the key points of comparison for parents is about values, then let’s talk about values, particularly, misconceptions about them. The belief that private schools have a more pristine embedded set of values than public schools is entrenched and must be challenged because it is untrue and offensive. In fact, any talk of values in Australian schooling rings hollow when our own Government can’t uphold the very basic value of equality by committing to its own goal of providing “all young Australians with equality of opportunity that enables them to reach their potential and achieve their highest educational outcomes” (The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration).

A culture of dog-eat-dog.

Australia is now considered an “outlier” in that “no other wealthy nation concentrates disadvantaged children into disadvantaged schools like we do.” Inequality is now “baked into Australia’s education system,” and by “deliberately starving the nation's public schools of vital funding,” social segregation in our schooling system is amongst the highest in the world. Data from the OECD shows that “students are sharply divided by class.”

Clearly, we risk becoming a nation where a ‘fair go’ in schooling is afforded only to the Prue and Trude’s – or at least the Kath’s and Kim’s (and Kel’s) willing to work two jobs to afford it. We once elevated humble, working-class heroes like Darryl Kerrigan from the movie The Castle, who embodied values of fairness, respect, and honesty. Now, we have a system where Darryl’s wage would help to fund literal Scottish baronial castles in exclusive private schools. I just don’t reckon he’d like the vibe of that.

In England, where private schools are in decline and are not publicly funded, one mother on blog Mumsnet.co.uk used a car analogy to justify her views on why parents choose a private school: “People pay the fees for a reason. Would you drive a BMW or a Nissan? If money is no object, possibly a BMW, right? People pay for a BMW for two reasons. One is they can afford it and two is they like it.”

Fair enough.

Drive any car you like.

But to use her analogy, the damage in Australia has come from systemic, unfair advantages between BMW’s and Nissan’s (so to speak) over decades. Imagine Nissan’s are running on empty and desperate for petrol and tune-ups, while roads (or parliament or the national rugby team) become chock-full of BMW’s. This skewed system is what’s already led to us having one of most socially segregated school systems in the OECD. The segregation by class, religion and race makes “it more difficult for children to develop a real understanding of people of different backgrounds and to break down barriers of social intolerance.”

Essentially, it appears we face a future where we no longer celebrate (or care about) the underdog. Instead, we fund a dog-eat-dog system fuelled by what Christine Ho describes as a “society-wide obsession with competition and choice in education.” Put simply, Australia’s public schools, which enrol more than 80% of all disadvantaged students, are doing more with less while facing a lingering image problem about an apparent lack of values.

The values thing.

Where did this flawed perception originate? Well, former Prime Minister, John Howard (himself educated in a public school), might have something to do with it. Back in 2004, he claimed that the rise in private school enrolments was based on what he “loosely called ‘the values thing’,” suggesting that government schools are "too politically correct and too values-neutral." Not only were his comments controversial, but they did lasting damage to the reputation of public schools. They were also farcically contradictory, as pointed out in a piece from the Age in 2004; “How can state schools at once be politically correct and values-neutral? Being politically correct implies having certain values.”

But who cares about logic when you have a culture war to fight?

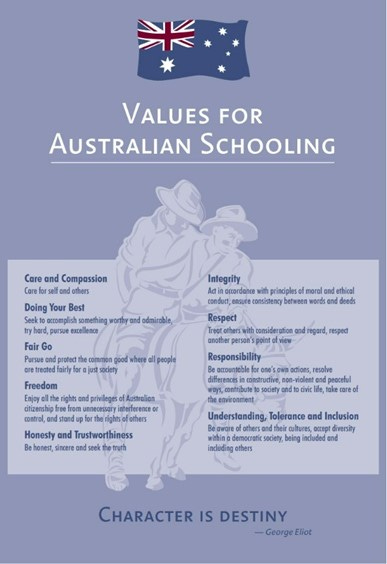

Subsequently, Howard launched a $31 billion-dollar federal education package to improve values which would tie school funding to a “National Values Framework.” For schools to receive any share of that money, they had to have a "values for Australian schooling" poster displayed prominently around the school. The poster was designed by Minister for Education at the time, Dr Brendan Nelson. It included a silhouetted image of John Simpson Kirkpatrick, the iconic stretcher-bearer from the Australian Army Medical Corps at Gallipoli, who with his donkey rescued wounded soldiers.

His image was accompanied by nine values: care and compassion; doing your best; fair go; freedom; honesty and trustworthiness; integrity; respect; responsibility; and understanding, tolerance and inclusion. My dad, Brian Ralph, was a public primary school teacher and principal for over 40 years and remembers the roll out of the values framework. “You had to put them up in your foyer and they had to be up in every classroom,” he recalls. “You also had to sign off that you’d done it so that they had a proforma document that went back to head office. Head office would then forward it on, and the funds would flow.”

He adds that because of Howard’s rhetoric about values being a key driver of parents leaving the government system, the framework approach was not only “top-down and heavy-handed,” but “it made assumptions that there were no values in public schools, which was palpably wrong.” In other words, he says, “without yelling it out, [Howard] almost suggested that public schools are in essence value free zones. That was particularly galling.” Nelson felt the poster represented “everything that’s at the heart of what it means to be Australian.” Never mind the fact that John Simpson Kirkpatrick was British and known to have left-leaning political views, writing in a letter to his mother:

“I often wonder when the working men of England will wake up and see things as other people see them what they want in England is a good revolution and that will clear some of there (sic) Millionaires and lords and Dukes out of it and then with a labour Government they will almost be able to make their own conditions.”

Mired in inequality.

Evidently, if he were alive today, Simpson might have some pretty strong views about the fact that we now rank in the bottom third of OECD countries in “providing equitable access to quality education” due to decades of Government underfunding of public schools.

Yes, Howard’s sentiment festered into the 2000’s, with the Abbott government unabashedly declaring their ''emotional commitment'' to private schools, with former Education Minister Christopher Pyne telling Christian school leaders in 2014 that it was his view the government had a “particular responsibility for non-government schooling that we don't have for [state] government schooling.''

Heck, at least he was honest. That counts for something, right?

So what is at the heart of being Australian if we now have a system “mired in inequality” which impacts “young people with disabilities, First Nations peoples, those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, students in regional and remote communities, and young refugees and asylum seekers the most”?

Imagine how those parents and teachers feel knowing that their tax money will actually contribute to private schools in NSW being over-funded by $382 million this year.

If we apparently value integrity, let’s talk about integrity. Consider Brisbane Grammar School. Last year, they raked in more than half-a-million dollars in non-refundable application fees alone. Catering to about 1800 boys, they received $54.86 million in tuition fees in 2023 as well as an additional $8 million from the federal government and $4 million in state funding. Meanwhile, at a school like St Ives in NSW, “parents are being asked to fund wellbeing programs, shade cloths, textbooks and buses.” Imagine how those parents and teachers feel knowing that their tax money will actually contribute to private schools in NSW being over-funded by $382 million this year. Surely most Australian’s would agree with the late David Zyngier that “elitist schools across Australia charging over $20,000 in fees do not need public money”? Afterall, David points out, “it’s not government funding, it’s taxpayer funding.”

It’s hard to see how a ‘fair go’ was offered to the NSW Department of Education recently when they dared to place in ad in the back cover of the Sydney Morning Herald’s 2024 Independent Schools Guide. The ad featured the slogan “the best education money can’t buy” to encourage parents to consider a public school for their child. It turns out some in the independent schools sector were so “unimpressed” to share their magazine with a public department ad that the Nine marketing team had to get its “mops and buckets out” in full “clean-up” mode; offering a sincere apology to the independent schools who paid thousands of dollars to appear in the guide.

What was so offensive about this ad being (apparently accidentally) published? If education departments aren’t able to promote public schools as viable and reasonable options for families, then how can they challenge the torrent of negative media coverage which is so often unfair and inaccurate? Apparently, the ad led to a roundtable with senior SMH staff and representative principals to discuss the publication’s commitment to a parent’s choice to educate their children in a learning environment that suits their “family’s values.”

But how would we even know if private schools are enacting these ‘family values’? For instance, Former NSW education minister Adrian Piccoli believes “many parents make a high school decision based on perceptions of student behaviour, or of a school’s level of discipline,” but he says he doesn’t “think the playing field is even…because Catholic and independent schools don’t have to provide that kind of information, and that gives them in a sense a marketing advantage. If Catholic and independent schools were also subject to freedom of information applications, that would make it a bit more equal. Public schools are much more publicly accountable.” Dr George Variyan and Jane Wilkinson agree, saying that “if elite private schools are run like ‘businesses’ and ‘bad news’ can spread, then it stands to reason that market pressures might lead administrators to play down or ‘disappear’ sexual harassment before these incidents come to parents’ attention.”

I believe most Australians who value fairness would want transparency in any school which receives government – sorry, taxpayer – funding, as well as inclusive enrolment practices. Dr Catherine Smith from the University of Melbourne’s graduate school of education notes “we see private schools are most likely to close their doors [to disabled students], saying they don’t have facilities, or the right training.” This practice of ‘enrolment gatekeeping’ is illegal under the Disability Discrimination Act (1992), yet “it remains a persistent issue in Australia.” In contrast, Helen Proctor says “the schools that have the strongest anti-discrimination values…are actually the public schools.”

A good revolution.

While there was widespread political backlash about Christine Holgate gifting Cartier watches as bonuses to senior managers of Australia Post in 2020, and community outrage when it was revealed that “billions of taxpayer dollars were wasted on businesses that saw an increase in their turnover during the pandemic instead of a decline,” it appears our moral compass is selective when it comes to the widening funding gap between public and private schools across Australia.

While it’s certainly refreshing to see an Education Minister like Jason Clare rock up to public schools for photo ops and champion the value of public schools, our moral compass is entirely broken when it comes to school funding. Chris Bonnor describes Clare as “the best chance at the right time” for improved school funding, but while “full SRS funding is critical,” we must also focus on dismantling a system that “consistently divides.”

We need what Simpson called a ‘good revolution’ to level the playing field and reflect deeply on what our values as a nation really are.

Till next time,

Great piece, thanks for writing! As a life-long and passionate advocate of universal, free public education (at all levels of our education system) perhaps the thing that bugs me the most about the concept of values and moral imperatives driving parents opting into the private system is the disingenuousness with which people defend their choice. While people will publicly claim they’re opting out of the public system, the sector that serves and strengthens our collective community and indeed democracy (Dewey, anyone?!) for all sorts of reasons, the bottom line is that they are buying their kid the right contacts and cultural and social capital.

Well said. Public schools are full of talented people getting so much amazing work accomplished on the smell of a oily rag. Far from values-free, egalitarianism and tenacity (at least) are values I'd say are infused in our public schools. I don't see how schools that charge a fee can claim to be developing either of those values. Asking families to pay to enrol surely excludes several such value claims from being made.