The competing ideologies surrounding education give the emphasis to everybody’s interests except teachers’: the needs of the child, ‘parental choice’, the needs of industry, the workers, the interests of society. There is constant pressure on teachers to sacrifice their interests to those of the kids, variously interpreted - Raewyn Connell

Education is at risk of losing the very people it needs to sustain itself.

Teachers1.

The UK knows it and we should too by now.

Teachers are burnt out and feeling less safe in their workplaces. The effect of misogynistic “manfluencers” upon Australian boys are intensifying the safety concerns of women teachers in Australian schools, causing them to leave the profession. These kinds of experiences are not isolated to teachers though, as we continue to see a growing number of principals experiencing burnout, threats and violence.

More recently, Australia’s perceived disruptive classrooms have been blamed for teacher attrition. A suggested solution to improve the retention of teachers has been to explicitly teach teachers classroom management strategies through an initiative titled “Engaged Classrooms” (which I have written a little about in the blog post below).

However, I am quite convinced this will not do enough. Teachers are not just leaving because they’re lacking in classroom management strategies, burnt out or feeling less safe, but also due to a lack of satisfaction in their work.

We need to address the root of the issue.

In this post, I wish to explore the possibility that issues of teacher burnout, safety concerns, and attrition (among many others) can be traced to an ideological framing of education that places student learning as the central (and possibly only) concern of teachers, leaders and the broader Australian community.

Teacher silence.

The above comment might seem a little silly.

It’s all about students and their learning, right?

But often our educational policy and discourse in relation to education, teaching and learning tend to forget a very important part of the picture.

The teacher.

Take for example Australia’s education declaration, which states that:

“Young Australians are at the centre of the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration” (Berry et al., 2019, p. 2, emphasis added).

The Australian Education Act describes education in this way:

“A good education prepares students for full participation in society, both in employment and in civic life” (Department of Education, 2020, p. 1, emphasis added).

Interestingly, the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership state the following on their website:

“At AITSL, we believe that student learning comes first. We're committed to improving teacher expertise” (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2017, emphasis added).

What can be seen here is a notable silence in relation to the needs and desires of the teachers themselves, who are integral to the success of education. The omission of the teacher from such statements about education tells us something about where the teacher stands in relation to the educational priorities of such policies and organisations.

Ideologically defining education as a student (or learner) centred endeavour implies that teachers are subservient to such purposes. A teacher’s desire to grow, experiment or shape students through their professional practice thus becomes, at best ignored, and at its worst quashed in favour of mandates and directives of what is perceived (often by others outside of the classroom) to be the “best” for their students.

Should we then be surprised that teachers are burnt out, taken advantage of, and are experiencing abuse in the classroom and through the media? Teacher bashing becomes “the norm” because of the unintended consequences of the “common sense” notion that education is simply about students and their learning.

Therefore, the kinds of omissions of teacher voice and identity that we currently have in policy contribute to the “constant pressure on teachers to sacrifice their interests to those of the kids” (Connell, 1985, p. 202), as teachers become implicitly framed as self-sacrificing individuals of a vocation that places the needs of others above themselves.

The missing link.

Placing students at the centre of educational policy and discourse is not necessarily a bad thing. However, one of the core reasons we’re seeing declining numbers of teachers is due to the continually increasing workload that teachers have had placed upon them over time and have largely (until recently as more continue to leave the profession) bore as a result of their passion and calling in relation to teaching.

But we now know, as teachers continue to hang up their boots, that a sustainable vision for education will need to take into account the hopes, desires and wellbeing of teachers.

When we don’t safeguard the desires and identity of teachers in policy and discourse, it can become difficult for teachers to develop a justification to challenge the various directives that are forced upon them. Sadly, this leaves room for the possibility of exploitation, where, for example, teachers become expected to give up their weeknights or weekends to meet the ever-growing demands of their role.

After all, it’s all about the students.

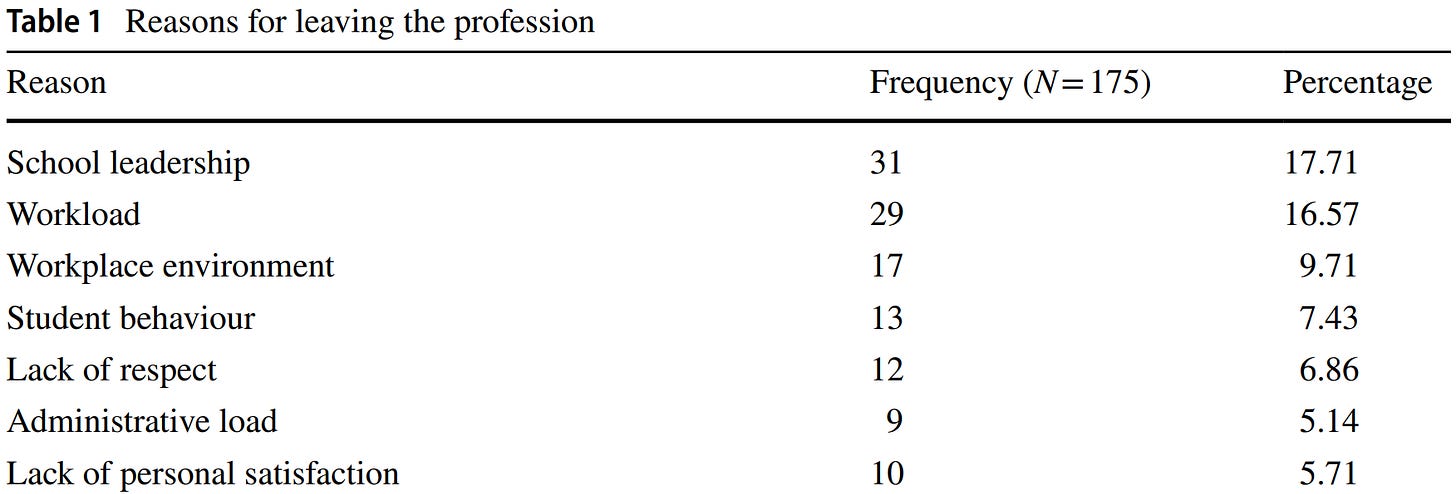

Below is an excerpt of a table of findings from a study of ex-teachers in Australia, showing the top seven reasons for teachers deciding to leave the profession.

“ex-teachers stated that they did not feel respected, and their work had failed to bring about or sustain the level of personal satisfaction they sought from their careers.”

As teachers continue to hang up their boots due to these ongoing issues, a sustainable vision for education will need to take into account the hopes, desires and wellbeing of teachers.

It’s time to bring teachers back to education.

Bringing teachers back to education.

It is my argument that if there is any way of increasing the retention of teachers in Australia, it will be through firstly acknowledging the importance of their wellbeing, desires and hopes in policy.

Policy describes what we believe is important to retain, but also provides a system of accountability. Therefore, if we were to truly believe in the importance of teachers, we would place them clearly in policy and hold systems to account to ensure that teachers are being valued.

I am not saying here to make teachers the centre of education.

But they are important, people love to say it.

Let’s put it in writing then shall we?

What I am saying is that policy needs to acknowledge the humanity of teachers as agentic professionals, who, rather than simply implement mandates and directives, require a degree of freedom to make the critical judgements needed to support not only their students and schools, but the growth of themselves as educators and professionals.

Teacher’s desires and hopes for their practice and lives need to be incorporated into our ideas of education. Otherwise, we will continue to lose great teachers as they become fed up with sacrificing their aims and purposes for education with whatever party is in power or whoever feels they have the “science” behind them.

Teachers have been expected for a long time to work extra hours, go on camps without extra pay, work on weekends, etc.

It’s been part and parcel of the job.

Interestingly, it is only now with the recently introduced time in lieu for Victoria are we really getting a sense of how much teachers have given to their profession above and beyond their contracted hours. These sorts of policy changes are making things hard, and so they should. They’re certainly not perfect, but these kinds of changes are in reality making it hard to take advantage of teachers. They are bringing to light the powerful impact of framing education as entirely centred upon the needs of students.

Using both eyes.

In this post, I have tried to show how issues of teacher respect, satisfaction and attrition can be traced to a relative silence of teacher desires in policy. By ideologically framing education in Australia as entirely centred around the needs of students and their learning, the door has been left ajar to use teachers in any way necessary to meet this vision. Often to their detriment.

As we continue to lose great teachers in Australia, I have argued that a possible way forward is to place the needs of the teacher as an important goal of Australian education into policy. Doing so would make a clear statement of the value of teachers in the success of educational outcomes and keep systems accountable for addressing ongoing teacher needs.

Whilst I have argued for the importance of considering teacher needs in how we construct educational policy, this is also a valuable exercise to be undertaken at the local level, such as how schools might run and keep one eye on the students and one eye on their teachers. If schools don’t do this, they may not see their own teachers heading out the side door.

Education is about students, yes.

It is also about teachers.

Let’s bring them back into the discussion.

Till next time,

References

Australian Institue for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL). (2017). About us. Retrieved 2nd May https://www.aitsl.edu.au/about-aitsl.

Berry, Y., Tehan, D., Mitchell, S., Uibo, S., Grace, G., Gardner, J., Rockliff, J., Merlino, J., Ellery, S. (2019). Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. Council of Australian Governments.

Brandenburg, R., Larsen, E., Simpson, A., Sallis, R., & Trần, D. (2024). ‘I left the teaching profession … and this is what I am doing now’: a national study of teacher attrition. The Australian Educational Researcher.

Department of Education. (2020). Australian Education Act 2013. Australian Government.

I should add that it seems that a number of initiatives announced by the current federal Education Minister, Jason Clare, are looking promising for future aspiring teachers.

Great piece here Tom. "Policy needs to acknowledge the humanity of teachers as agentic professionals, who, rather than simply implement mandates and directives, require a degree of freedom to make the critical judgements needed to support not only their students and schools, but the growth of themselves as educators and professionals." Excellent quote. It's great to read an article on the relative silence on teachers wellbeing and agency - yet there's so much shock and head scratching as to why so many are leaving. I note your chart you use here has school leadership as the number one reason for teachers leaving, which tells us that it's likely both eyes are on the students most of the time. By the time they look up and refocus on teachers they may be surprised to have fewer and fewer.

Really enjoyed this one Tom, especially the idea of 'two eyes'. Have noticed it this week in planning conversations, doing a pivot after discussing student impact to teacher impact. Different decisions are definitely made.