Learning doesn’t start at the school gates.

Why are we so worried about it then?

There is more to life than learning - Gert Biesta

Recently, NAPLAN results came out.

Along with its release, the media predictably depicted Australian education in a dismal state, with think-tanks such as Grattan Institute conflating achievement in a single-point standardised test with the health of the schooling system at large.

These reports are often partnered with calls for more.

More reform, more standards, more accountability, more explicit instruction, more phonics, more testing…The list goes on.

Teachers, viewed as causal influences on learning, become entangled in what seems like a never-ending barrage of reform agendas, which often overlook important external factors impacting on student achievement in schooling. The faith that improving teacher quality (however defined) will cure societal problems seems to blind many to the possibility that such problems lie beyond the control or responsibility of the teacher.

This post will explore a basic ideological perspective driving much educational policy, discourse and practice in our current time. That is, the idea that students must have as much knowledge and skills stored in their long-term memory as possible before they leave the school if they’re to succeed in the world.

Furthermore, I also seek to highlight how understanding this as the core responsibility of teachers is deeply problematic.

Seems logical but ultimately ideological.

The idea that schooling must fill student’s minds with as much knowledge as possible before they enter the “real” world seems like common sense.

But it is deeply ideological.

By using the term ideological here, I am making it clear that such a perspective ultimately forms a political belief of how education ought to function.

Although rarely acknowledged, the value judgement made when discerning what education ought to do is always ideological. This holds true for those who might see education as requiring efficiency, or for those who desire for education to produce resilient learners or workers for industry needs.

Learning doesn’t start at the school gates.

In educational policy and discourse, there seems to be an underlying fear that if students don’t meet the arbitrarily defined benchmarks of knowledge (otherwise known as the curriculum) by the time they leave school they will be doomed to live life as a second-rate citizen.

This fear is based upon assumptions regarding what schooling can do for its students and society as a whole. It assumes that the curriculum secures success in the world and the workplace.

Anything less is a crisis.

This is worth questioning, considering the potential emotional toll that this kind of responsibility places upon a profession that is already buckling under the weight of current systemic pressures.

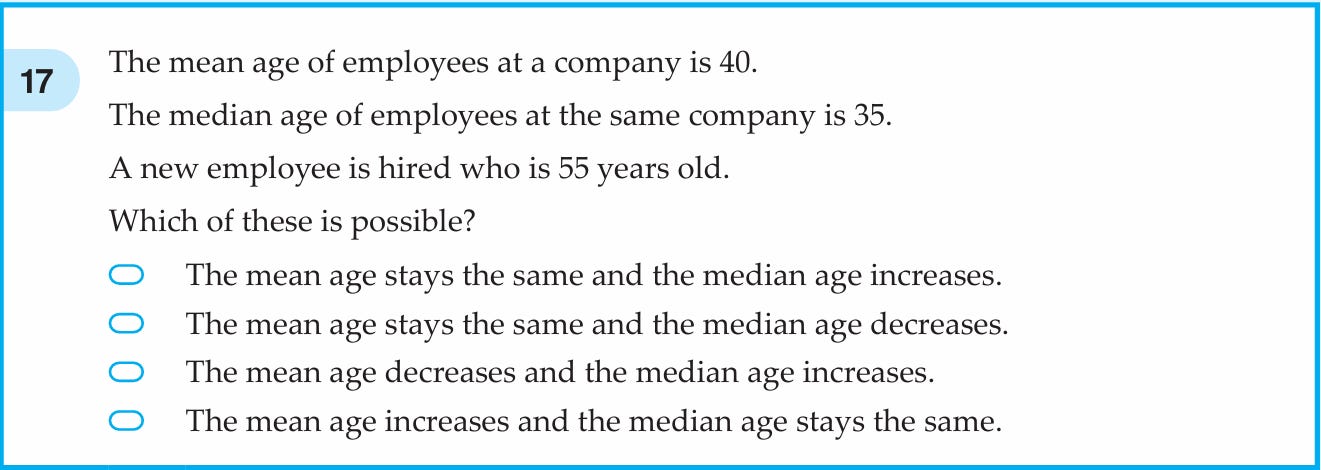

Let’s take for example this question, extracted from a 2016 NAPLAN Year 9 Numeracy test paper1:

Yes, understanding the important difference between the mean, median and how the inclusion of new values might skew these measures can be valuable.

But should we be concerned about the health of Australia’s education system if such questions are not answered correctly? Is Australian Mathematics education in crisis as a result?

Learning never started with the school, nor will it end with it. It certainly was never limited to a couple of measurements in literacy and numeracy.

Yes, this is one question and not representative of the entirety of NAPLAN testing.

However, give a quick glance through the list of 2016 NAPLAN test papers and it becomes evident that failure to succeed in such tests (however you define success here) need not lead to unnecessary anxiety surrounding our young Australian’s ability to contribute to society.

Teachers can, and already do, give their best to support their students to retain and apply the knowledge and skills they develop in schooling effectively.

Let me reiterate this, Australian teachers do excellent work.

But the narrative presented in media reporting of NAPLAN suggests that Australian society as we know it is doomed unless we make drastic policy changes towards explicit teaching and “what works”. It is assumed that students need to retain more measurable knowledge and skills in order to improve Australia’s prospects.

Why are we so caught up in fear surrounding this? Learning never started with the school, nor will it end with it. It certainly was never limited to a couple of measurements in literacy and numeracy.

Like a recently immigrated teacher from Canada once said to me:

“I don’t understand why you guys are in crisis all the time. Things are pretty good here.”

The kind of society the school needs.

In a statement after first receiving the role as federal Education Minister, Jason Clare stated:

“What we do in our primary schools and our high schools, if we get it right, really sets the Australian economy up for the next decade and the decade beyond, making sure that our kids have the skills they need for the jobs of the future.”

Can we really place responsibility for the Australian economy for the next two decades upon the shoulders of teachers and schools?

Although well-meaning, such statements create an expectation for teachers and school communities that is not only unreasonable but also potentially damaging to our collective understanding of education.

If we really want to “get it right”, we should begin by questioning the ideological assumption that there is some arbitrary amount of general curriculum knowledge and skills that all students must store in their long-term memory in order to succeed in society.

From there, we can consider what role parents, families, workplaces, social media, further education institutions and society as a whole have on the contribution to the education of all Australia’s young people.

Yes, education is a lifeline.

Yes, education can open doors.

Yes, education can transform lives.

But education is never done by the school alone and learning never started at the school gates.

We might declare that we want an education system that is set up in such a way that every student can be the very best they can be.

But is our society set up to allow this?

Till next time,

Sadly, NAPLAN tests are no longer released to the public since moving to an online platform.

Great article, Tom. I love that the Canadian teacher says, "I don’t understand why you guys are in crisis all the time. Things are pretty good here.” So true. Get this on LinkedIn asap let's get it circulating! Love this: "The faith that improving teacher quality (however defined) will cure societal problems seems to blind many to the possibility that such problems lie beyond the control or responsibility of the teacher."

I’m reminded of Diane Reay arguing simply that education cannot compensate for society. The strange and disturbing thing, however, about our times is that we’ve seemingly adopted a perverse and irrational, indeed schizophrenic, interpretation of this statement. Schools are expected to not only compensate for society but pretend that society doesn’t really exist. I would describe this as the frightening result of decades of social erasure by neoliberalism, acculturating us to not think or question, the presumption being we exist in an ahistorical vacuum of sorts. Depoliticising teachers and teaching to ensure that kids are drilled with approved standardised curriculum through pedagogical practices designed explicitly to deny agency and hammer out creative thought will only make us all dumber. But I guess that’s not an ideological objective, but only pragmatic.