Ignoring evidence.

It all comes down to ideology.

Now you’re looking for the secret, but you won’t find it, because of course you’re not really looking. You don’t really want to know. You want to be fooled - Christopher Priest

A dual movement.

There seems to be a dual movement happening at the moment in Australian educational discourse and policy.

At the very same time that educational policy and practice is being praised for purportedly becoming more “evidence based”, we are seeing an increasing disregard for important, alternative and valid evidence.

In this post, I will present two examples that highlight the presence of this dual movement. The first referring to recent initiatives claiming to “save teacher time”, which no one asked for. The second being the reform agenda to place high priority to systematic-synthetic phonics in primary schools, which we have evidence to suggest it really doesn’t provide the “revolution” it promises.

Let’s go.

Time is money.

Australia has gone deep into the creation of ready-made lesson plans for teachers as a solution for many of our educational woes.

Big money is currently being spent in Victoria and New South Wales in a bid to ease teacher workloads, with claims that such resources will free up teacher time and improve learning outcomes of students (Australian Government, 2023).

Sure, having lesson plans to work off as a starting point are a great idea, but where is the solid evidence to suggest that outsourcing lesson creation will achieve what it is promised to?

Are we forgetting that Queensland had already gone down this path over ten years ago with no real evidence of success? I also recently heard a rumour1 that South Australia is abandoning their lesson plan initiative, which began in 2019.

If these initiatives were so successful, you would have heard about them.

Rather than listening to the thousands of teachers surveyed who indicated that they valued lesson creation and developing policy to encourage and facilitate this, policymakers have ignored teachers in favour of the questionable advice of think-tanks to outsource this important work in a bid to ensure “quality”. It is important to note that although it is positive that these lesson plans are not mandated (yet), what is concerning is the way that such policies send subtle ideological messages about what good teaching ought to look like. It has the potential to limit education to a formula, which when adopted with fidelity is assumed to reliably result in desirable outcomes2.

Sure, having lesson plans to work off as a starting point is a great idea, but where is the solid evidence to suggest that outsourcing lesson creation will result in what it has been promised to achieve?

The video below shows an example of one of the lesson plans developed for the Year 8 Level Victorian Mathematics curriculum, you can also have a look yourself here.

Keeping in mind this is for a single, 1-hour mathematics lesson.

I should preface this by saying, as an experienced teacher I am always open to looking at other teacher’s ideas and ways of structuring lessons.

But I ask again, do we have evidence that lesson plans like this are going to reduce teacher workload (besides the limited evidence provided by vested interests)?

On average a full-time secondary teacher in Victoria has approximately 30 minutes of planning time per hour of teaching time3, how long do you think it would take for a beginning teacher to digest and enact these lesson plans?

Worth a thought.

With all the recent hoo-ha surrounding cognitive load theory as a central idea in teaching, I’m wondering what John Sweller would have to say about all of this.

Phonics fixation.

More recently, Australian policymakers have embarked on a phonics frenzy by mandating systematic-synthetic phonics (SSP) instruction and a Year 1 phonics check, justified on the basis that the “science is settled” and the “weight of evidence…has become clear and compelling”.

These reforms are strikingly similar to changes made in the UK in 2017.

How did that pan out?

Not great.

Professor Cathy Wallace from University College London is quoted here stating that:

“UK students’ performance in reading was at its highest in 2000, before the heavy emphasis on phonics. Children in the Republic of Ireland and Canada, where synthetic phonics isn’t as central, outperform their British peers in reading.

And in general, England’s PIRLS scores – as well as other data – show that achievement in reading has stayed fairly stable since 2001, rather than showing the improvement that might be expected if phonics was indeed so effective.”

Even more concerning is that in the UK, reading enjoyment amongst children and young people is now at its worst ever recorded level.

But wait, there’s more.

It’s not just the UK who have experienced broken promises of SSP.

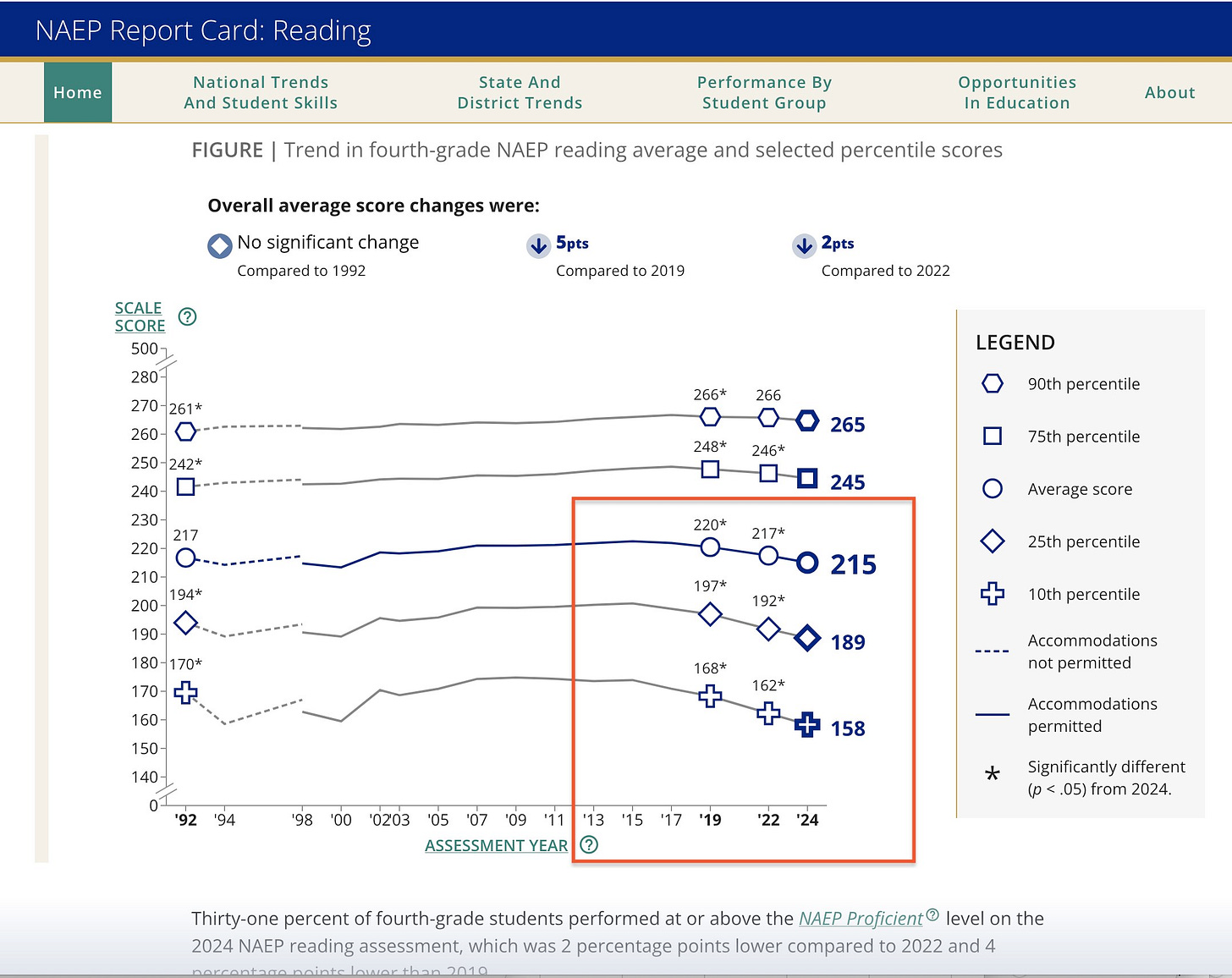

The US is also hurting from the same condition (see in the image below the highlighted box indicating the “science of reading” era).

Makes me wonder whether we are we looking at the right evidence.

Selective hearing.

I have provided two examples of a growing prevalence of selective hearing in contemporary educational discourse, but there are loads more4.

By providing the two examples above, I have highlighted instances where important evidence is being ignored in favour of pre-selected “experts” and cherry-picked evidence, conveniently providing the justification for educational reform in Australia.

Why is this?

These decisions all fundamentally arise from ideological positions, not evidence.

See, the evidence often doesn’t come first in education, ideology does.

The “evidence” we use to justify our decisions are commonly first drawn from ideological positions of what education, teaching and schooling ought to look like. It is from this grounding that we make judgments about which evidence to accept, the state of education and take action about what can be done to address perceived educational problems.

Ideological perspectives regarding the purpose (or “problems”) of education are often left unquestioned, which is why “crisis” rhetoric and calls for reform can be so convincing.

At times, it can be so convincing to feel as though there is no alternative5.

If valid evidence is being ignored, then it isn’t really about evidence.

It’s about ideology.

Till next time,

References

Australian Government. (2023). Improving outcomes for All: The report of the independent expert panel’s review to inform a better and fairer education system. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.au/review-inform-better-and-fairer-education-system/resources/expert-panels-report(open in a new window).

If you know of any information on this that would be very helpful! The South Australian department of education websites and its policies are incredibly opaque.

Education just doesn’t work like this.

I got this number from colleague of mine who crunched the numbers, happy to be corrected.

Know some? Why not add them in a comment below!

To quote Margaret Thatcher.