You can own everything that you are supposed to own in the modern world to be happy and satisfied and full of life and yet at that very moment, in some profound way, be possessing next to nothing - Rob Bell

In a recent post, Learning doesn’t start at the school gates, I explored a prevailing ideological perspective in education that believes that students ought to retain as much information as possible in their long-term memory before they leave school in order to succeed in the world.

The aim was to challenge the fear that students will not be able to contribute to society in a meaningful way if they do not have some arbitrarily defined minimum amount of knowledge (either real or perceived) before they leave school.

My hope is that such arguments might help to alleviate our worries surrounding the state of Australian1 teachers and schools in order to redirect our attention to other, much larger societal contributions to educational inequity.

This month’s post will further build upon this argument by exploring the potential for an obsession with knowledge acquisition to be in vain, as knowledge becomes implicitly understood as something that students are to accumulate rather than possess.

Let’s go.

The ideology of knowledge accumulation.

In our current age, knowledge accumulation risks becoming an unchallenged ideological goal of schooling, where the desire for an ever-increasing breadth of knowledge thins out curriculum at the expense of deeper understanding, critical thinking and other broader educational goals of schooling.

Does anyone actually set out to do this?

For the most part it would be safe to assume no, yet the structural elements of the Australian educational landscape have come to form a kind of hidden curriculum for teachers, implying that what is most valuable about education is the teaching and learning of content knowledge.

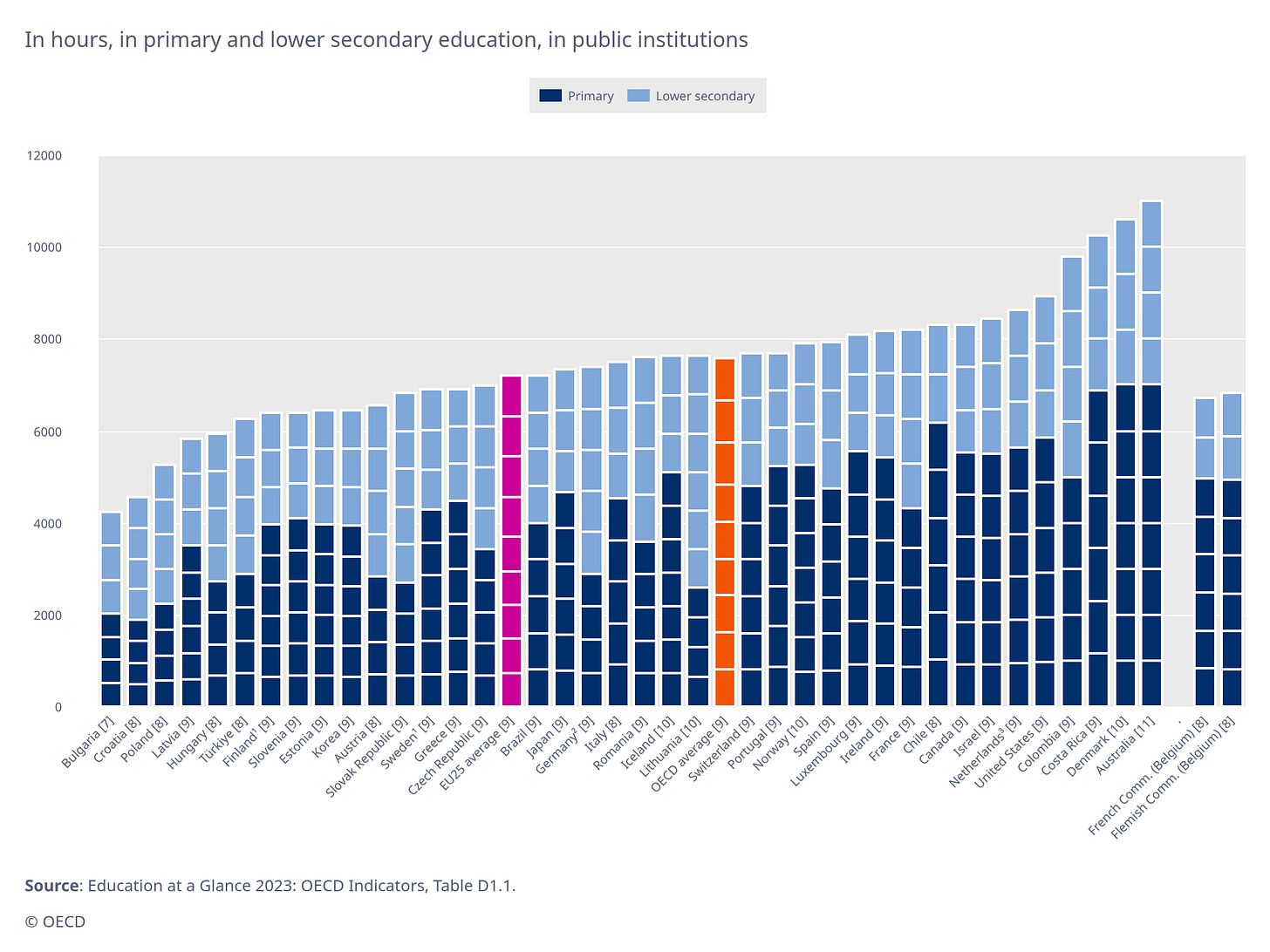

For example, students in Australia receive the highest number of compulsory school hours of any country in the OECD (below). Yes, there is certainly more to face to face school hours than learning content. However, what is more often than not done during such time? Teaching with reference to curriculum.

There also appears so little time for teachers to plan for the sheer breadth of the curriculum (with little interrogation into why this might be the case) that governments, organisations and companies across Australia are increasingly developing curriculum resources and materials for teachers in a bid to “save teacher time” (although the claim that such resources will save time is highly questionable).

Teacher time in the classroom, framed as in short supply (without critiquing the reasons for this) has become viewed as so precious that it requires the most efficient means of transmitting the ever-increasing amounts of core knowledge of the curriculum to all students. The importance placed on teaching time has led some to believe that it is too risky to allow teachers the agency to decide how such time is to be spent. As a result, education departments across Australia are mandating teaching approaches as the way to achieve this goal.

These examples subtly send the message to teachers that:

The purpose of schooling is to transmit disciplinary knowledge.

Accumulation of disciplinary knowledge is what our students and society need.

Predefined mandated curriculum is inherently complete and unproblematic. It is teachers who must adapt to the curriculum, rather than the other way around.

Any problems with knowledge transmission are ultimately a result of teaching practices.

As I said earlier, these may not reflect our actual desires for education.

Yet, ideology has a way of slipping under the radar. It can become the common sense that guides educational policy and practice, though it may never be explicitly stated in such harsh terms.

Brains full of junk.

I used to know a guy that liked to collect cars, only to house them away in a garage. He would not take them out for a drive for fear of possible damage.

A small loose rock could drop a car’s value by a significant amount; he would tell me.

But what do we call something that is never used except junk2?

In an ideology of knowledge accumulation, like the fearful car enthusiast, we risk learning a lot of stuff but doing nothing with it. In this scenario, knowledge becomes old, unused and fragmented, disassociated from the reality of the student’s lives and left to slowly fade away in the dusty garages of our minds.

Beyond knowledge accumulation.

The great disappointment of such a view would be to see increasing amounts of time, energy and resources invested in trying to get students to accumulate knowledge, rather than supporting them to possess it.

Possessing knowledge is not limited to retaining information in long term memory. It involves the ability to use it, apply it, know who such knowledge benefits and how such knowledge is ideologically grounded.

In other words, possessing knowledge is about ownership and agency.

The perception of curriculum as a strict set of knowledge outcomes that must be achieved for every student has become ideological in that it has become unchallenged common sense across the Australian education system.

Is the holy grail of a guaranteed and viable curriculum truly possible with standardised curriculum, given the reality of increasing inequity and declining student attendance across Australian schools?

Is it possible to deliver the curriculum as intended, yet still fail to provide an education?

If we want to avoid the risk of schooling becoming limited to knowledge accumulation, pressure needs to be placed upon the structures that funnel practice towards it.

Teachers need to raise their voices3.

School communities ought to consider whether their approaches to curriculum are truly meeting the goals they wish to achieve with their communities through education.

This requires that we reflect on the most fundamental of questions:

Why?

Till next time,

Recommended reading

Biesta, G. (2025). Taking the Angle of the Teacher: The GTC Scotland Annual Lecture 2024. Scottish Educational Review, 55(1-2), 175-191. https://doi.org/10.1163/27730840-bja10014

Oberg, G. (2025). Queensland teachers are striking. It’s not just about money – they are asking for a profession worth staying in. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/queensland-teachers-are-striking-its-not-just-about-money-they-are-asking-for-a-profession-worth-staying-in-262496.

Hickey, C. (2022). A ‘crowded curriculum’? Sure, it may be complex, but so is the world kids must engage with. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/a-crowded-curriculum-sure-it-may-be-complex-but-so-is-the-world-kids-must-engage-with-157690.

But also including teachers and schools across the world facing similar circumstances.

I do appreciate that there are some holes with this analogy. However, I feel that even different takes of this analogy would have important parallels to how we see education.

thanks Tom, I recently heard Tom Loveless a prominent SoL advocate make interesting comments about the change of Maths curriculum: San Francisco initially mandated Algebra I for all eighth graders, aligning with California’s previous standards that encouraged early algebra. However, after adopting Common Core, the district reversed course and prohibited Algebra I in eighth grade, aiming for uniformity in math education as a form of equity. Loveless argues this approach backfired: affluent families could bypass the system by purchasing private tutoring or enrolling in external courses, while disadvantaged students—who relied solely on public schools—were left behind. The policy, intended to promote equity, ended up reinforcing inequality.